Meet the Minds: Dr. Rayjean Hung translates big data into better, more equitable health for all

In our Meet the Minds series, we’re opening the doors to the visionary researchers shaping the future of health care at Sinai Health. You’ll get to know the innovators behind the breakthroughs — their passions, discoveries and the impact they’re making on lives today and tomorrow.

Take a deep dive into the power of data with Dr. Rayjean Hung, Associate Director of Population Health and Head of the Prosserman Centre for Population Health Research at Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute (LTRI). Her work shows how harnessing big data can lead to earlier cancer detection, smarter screening and more equitable health outcomes for people of all backgrounds.

Q: How would you describe population health research, and what is its importance in cancer research today?

Dr. Hung: The goal of population health research is to reduce the burden of disease across entire communities. Unlike other medical research, we focus on large groups of people and look beyond treating people who are already sick to explore how to prevent diseases and keep people healthy.

By studying disease patterns in large populations, we can understand why certain diseases, like cancer, develop, who is at risk and what factors are driving these trends. Ultimately, this type of research can improve patient outcomes and even influence public health policy.

Q: What have been the biggest shifts in how we study cancer risk over the past decade?

Dr. Hung: One of the major shifts I’ve seen was revolution in technology. This field leverages heavily on technology, so the rapid development of new tools is significantly expanding what’s possible — especially in areas like cancer research. For example, we are now working with a tool called liquid biopsy, which lets us analyse small fragments of DNA that carry tumour information from a simple blood sample. So instead of needing to take a piece of the tumour with biopsy or surgery, we can now get that important information just from a blood sample.

Another shift is the growth of international collaboration, which plays a key role in my work. Collaborating across institutions, and countries, helps increase the power of our studies by bringing together larger and more diverse population data. This makes our findings stronger and more reliable.

Finally, advanced data analytics, especially artificial intelligence (AI), is helping us manage and make sense of the huge amounts of data we now collect.

Q: Why is it important to develop innovative ways to screen cancers earlier and more effectively?

Dr. Hung: Early cancer detection dramatically improves survival rates. When found early, treatment options are more effective, even curative, and the chances of living beyond five years are much higher.

Innovative screening methods are important not just for the individual, but for the healthcare system and society as a whole. Detecting cancer early means people can return to their lives sooner and reduces the strain on the health-care system. Ideally, we would prevent cancer altogether. But when that’s not possible, catching it early can save lives, improve quality of life and reduce the overall burden of disease.

Q: As a world leader in complex disease epidemiology who is involved in multiple projects, what’s the unifying thread that connects all your research?

Dr. Hung: My research focuses on cancer and maternal-infant health. These may seem unrelated, but they’re deeply connected by a common framework: early life experiences can shape health later on, and data can be used to translate discovery into real-world population health impact.

A key part of this is using large, multi-dimensional data sets. We collect molecular data like genetic and protein information and combine it with lifestyle, environment, medical history and imaging. This helps us understand disease risk and tailor screening and prevention strategies to the right people at the right time.

In lung cancer screening, for example, my research helped show that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease raises lung cancer risk — even in people who never smoked. It's evidence like this that can inform individual risk-based models, which are more accurate than typical age or smoking cutoffs and ultimately lead to the earlier detection of lung cancer in patients. In fact, lung cancer is the only cancer that is currently being screened based on such an individual risk model.

Another example is liquid biopsy. We found that certain changes in the blood (called epigenetic changes) can help show whether a tumour is present and where it started. This is now one of the most promising areas for liquid biopsy.

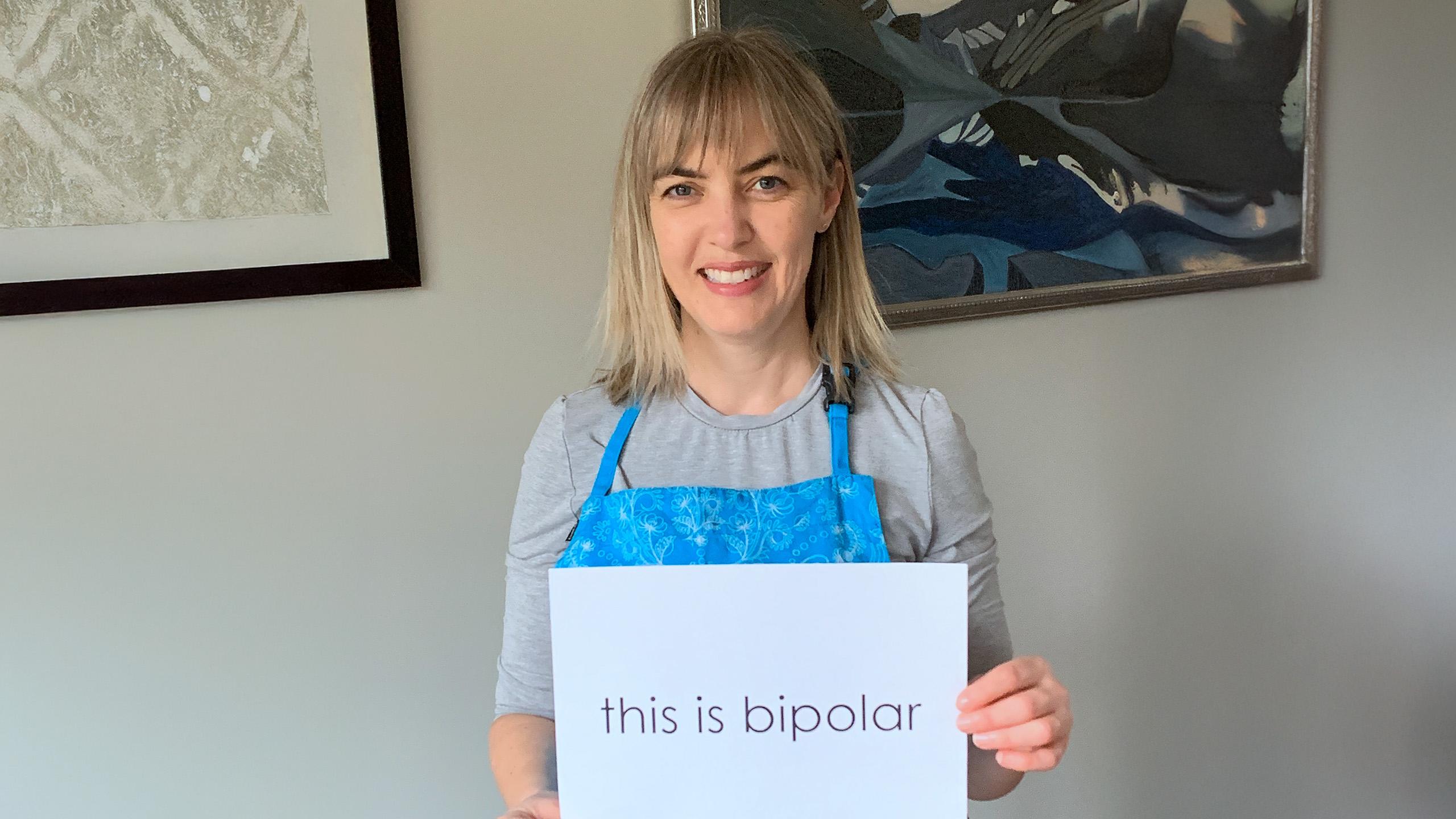

Q: How is your research helping to make cancer screening and prevention more equitable across diverse populations?

Dr. Hung: Historically, research on lung cancer in Black, Asian and other underrepresented populations has been limited which creates gaps in our understanding of disease risk and outcomes. To address this, we actively work to collect more data from these populations. This approach is rooted not only in scientific need but also in a commitment to equity, ensuring that our findings apply across diverse communities.

One major focus has been understanding genetic and molecular differences across ancestries. For example, we’ve found that genetic risk markers identified in European populations don’t always appear in Asian or Black populations due to differences in genetic structure. This is important because it helps ensure that risk prediction or early detection tools are accurate and effective for everyone, not just a subset of the population.

Q: What area of your research do you find most promising or exciting at this time?

Dr. Hung: The amount of data out there right now that can be used to help understand disease risk and trajectory is incredible — and we're just scratching the surface. We've just started to expand our scope beyond molecular data to include environmental exposures and planetary conditions, such as linking air pollution and climate change data with maternal and infant health. Once you know how to harvest satellite or environmental data like this, you can ask so many more questions in your research in a very cost-effective way with potentially wide-ranging impact.

Q: What advice would you give to young researchers – especially women and people of colour – who are interested in population health research?

Dr. Hung: Embrace all challenges! Population health research can be complex and slow-moving at times — it takes persistence and patience to uncover meaningful patterns. But the work is incredibly rewarding. You’re exploring data that can help improve the health of entire communities, even across generations.

To women and people of colour in particular — we need you in this field. We need a diverse range of voices to ask new questions, challenge assumptions and look at data in ways that reflect the realities of different communities. What you work on now has the potential to change people’s health trajectories in the future.

Want to support groundbreaking research like this? Donate today and help advance the next breakthrough. Please select Research - Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute from the gift designation dropdown menu.