Innovative ultrasound technique developed by Mount Sinai Hospital and SickKids researchers enables earlier detection of placental diseases

Placental diseases often implicated in stillbirths, serious illnesses of newborns, making early detection critical.

Researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital, part of Sinai Health and The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) have successfully taken their novel ultrasound technique from the bench to the bedside, demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting placental disease, which could ultimately help prevent some future stillbirths or serious illnesses in newborns. Their findings were published in eBioMedicine on May 5, 2021.

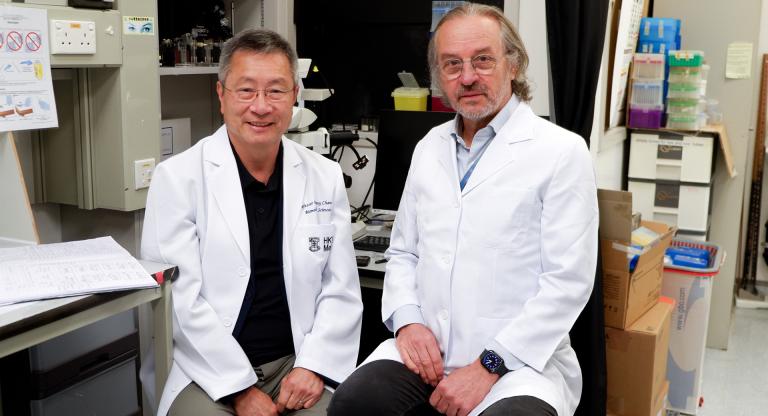

Issues with the placenta, also called placental diseases, are present in over half of stillbirths, which are defined as losses of a baby at or after 20 weeks of pregnancy, and cases of fetal growth restriction. Yet, common diagnostic methods are often inadequate at detecting certain types of placental diseases prior to birth. A research team led by Dr. John Sled, Senior Scientist in the Translational Medicine program at SickKids, has found a more precise way to measure umbilical cord blood flow. Their technique uses conventional ultrasound equipment that could alert physicians to potentially devastating issues in the placenta.

“One of the challenges with placental diseases is that they can get worse rapidly, so early detection is key to reduce the risk of stillbirth,” says Dr. John Kingdom, co-author on the study and co-director of the Placenta Program at Mount Sinai Hospital. “For instance, if we know a placental disease is present, we can increase monitoring of the mother and fetus or even deliver the baby earlier, which can result in a complete change of outcome.”

Two measurements are better than one

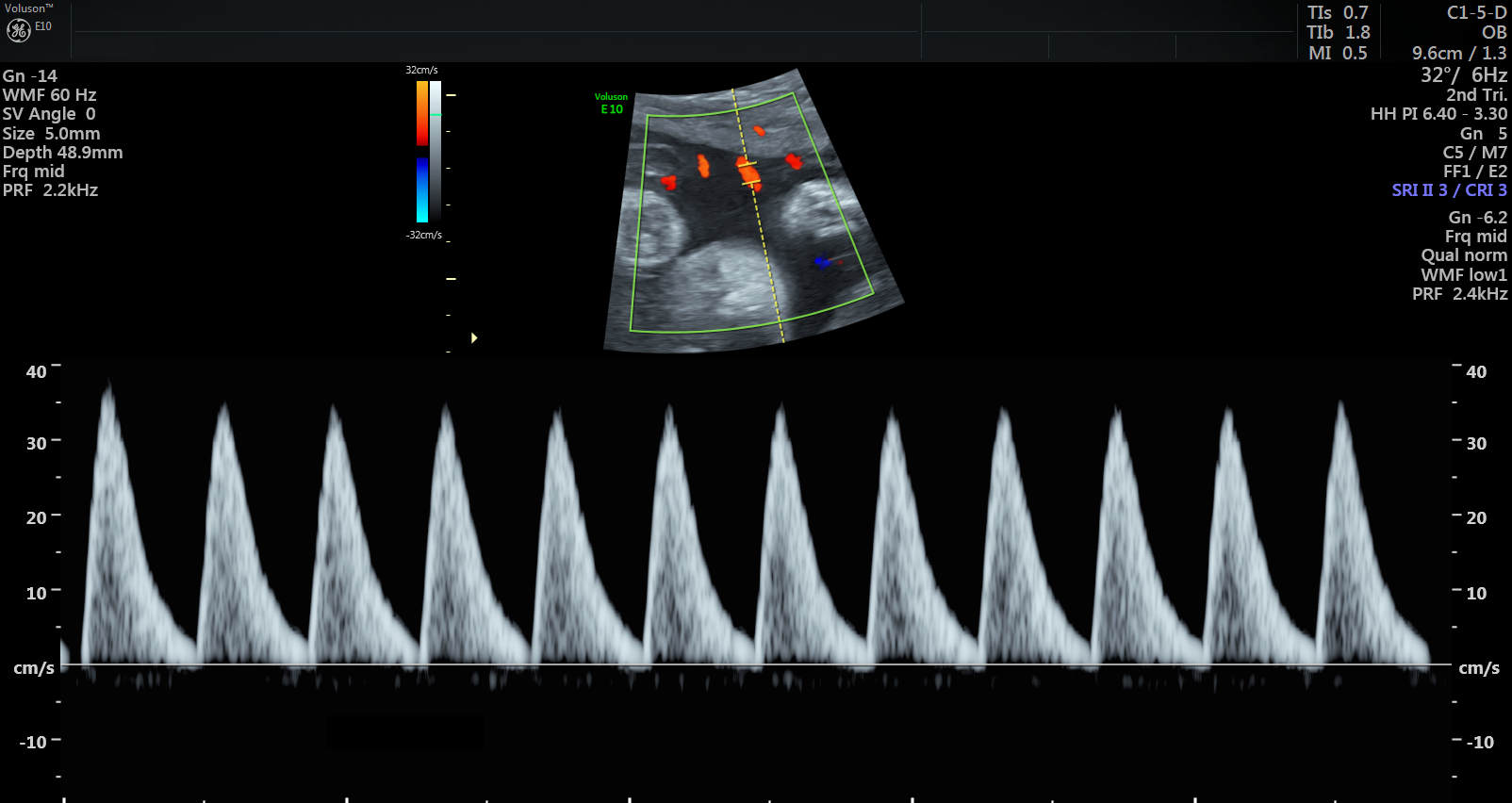

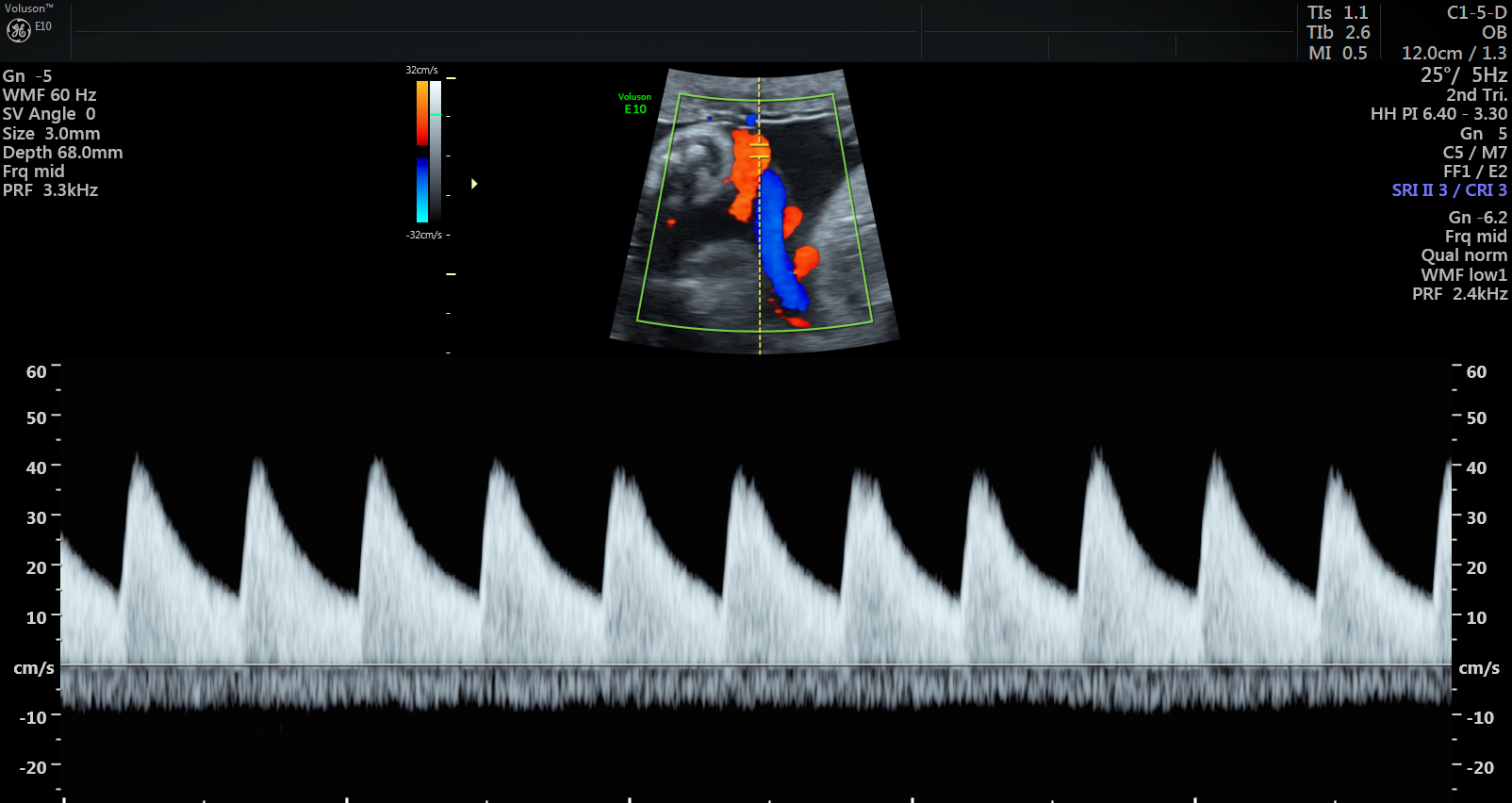

Currently, standard-of-care ultrasound scans measure blood flow at one point in the umbilical cord. The technique takes two measurements – one at the fetal end of the umbilical cord and one at the placental end. Sled says recording both measurements gives a much more accurate picture of the way blood is travelling through the umbilical cord.

“By looking at both measurements and the physics of how blood travels, we can get insight into how some of the finest blood vessels in the placenta are organized. The information this can provide to physicians is invaluable,” says Sled, who is also the Director of the Mouse Imaging Centre and a Professor and Vice-Chair in the Department of Medical Biophysics at the University of Toronto.

The placenta has two blood circulations, one attached to the mother and another attached to the fetus. If the disease is primarily affecting the maternal circulation, it’s called maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM) and if the fetal circulation is primarily affected, it’s called fetal vascular malperfusion (FVM). MVM is the most common placental disease associated with fetal growth restriction, where a fetus is smaller than expected, and is often the cause of preventable stillbirth. FVM is less common but also associated with fetal growth restriction and other adverse outcomes.

The study recruited almost 430 women through Mount Sinai Hospital and Johns Hopkins Medicine. The researchers used their technique on the women’s ultrasound scans taken between the 26th and 32nd weeks of pregnancy. 241 women had their placentas physically examined after birth to verify diagnoses, which confirmed that 30 of these women had MVM and 16 had FVM, diagnoses that were successfully made with the ultrasound method.

“Our hope for the future is that you could identify women with this type of placental disease in an early stage and refer them for more intensive follow-up.”

Adjusting delivery dates, increased monitoring could prevent poor outcomes

They plan to continue adjusting the technique to make it faster, more reliable, and ultimately translatable into any clinic.

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of Health Grant, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and SickKids Foundation.